TikTok, Teens, and Body Image: What Every Parent and Teacher Should Know

Why don’t I look like that?”

That quiet question—whispered by a student after watching a 30-second TikTok workout clip—captures the hidden cost of “fitspiration” content flooding kids’ social media feeds. While these videos are packaged as motivational fitness tips, new research shows they often do more harm than good.

A study from the University of Liverpool found that just a few minutes of TikTok’ fitspiration’ exposure left young adults feeling worse about their bodies. Body satisfaction dropped significantly after watching, and for girls, self-esteem took a sharper hit than for boys.

The kicker? This effect showed up after less than a minute of viewing.

What the Science Found

Researchers recruited 274 TikTok users, ages 18–62, and showed them either neutral travel clips or fitspiration videos featuring sculpted bodies in gym settings. They measured participants’ body satisfaction and self-esteem before and after.

The results were striking:

- Body satisfaction fell for both men and women after fitspiration exposure.

- Women reported lower self-esteem than men, both before and after watching the videos.

- The more accounts people followed, and the more they cared about getting “likes,” the more likely they were to internalize unrealistic fitness ideals.

In plain English: the TikTok algorithm rewards glossy, aesthetic-driven fitness clips. The more kids watch, the more they compare—and the worse they may feel about themselves.

Why It Matters for Schools and Families

Think of TikTok as a digital funhouse mirror. Kids don’t just see their friends or classmates—they see idealized versions of bodies, polished by lighting, editing, and filters.

This sets up what psychologists call “upward social comparisons.” In other words, students are constantly comparing themselves to “better” versions of other people. That comparison chip away at confidence, particularly in teens whose identities and self-worth are still taking shape.

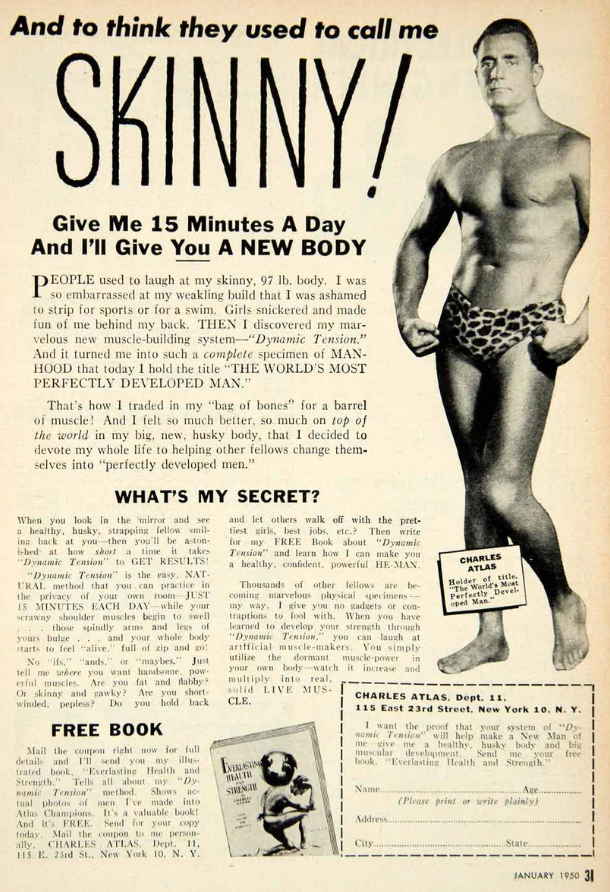

For girls, this often means greater self-objectification—valuing themselves based on their appearance rather than who they are or what they can do. For boys, the growing pressure is different but no less harmful: a push toward lean, muscular “superhero” physiques that few can realistically attain.

And here’s the school connection: lower self-esteem and body dissatisfaction aren’t just “feelings issues.” They spill directly into learning. Distracted students struggle to focus. Kids who feel bad about their bodies may withdraw from gym class, avoid raising their hands, or even skip school altogether.

The Hidden Role of “Likes”

One fascinating twist in the study? It wasn’t just screen time that mattered. It was how emotionally invested kids were in likes and follows.

Students who deeply cared about getting validation through hearts and follower counts were more likely to internalize TikTok’s body ideals. This suggests that the problem isn’t only exposure—it’s how much young people buy into the platform’s currency of approval.

Turning Research into Action

So, what can parents, teachers, and school psychologists do?

- Talk About TikTok, Don’t Just Police It

Instead of “no screen time” rules (which rarely stick), ask kids about what they’re watching. Encourage them to share how certain videos make them feel. - Promote Function Over Form

Researchers highlight “functionality appreciation”—teaching kids to value what their bodies can do (kick a soccer ball, carry groceries, dance in gym class) over how they look. Celebrate effort and capability, not just appearance. - Integrate Media Literacy into Classrooms

Schools can expand digital literacy programs to include body image awareness. Students should learn to spot when a video is pushing an unrealistic standard. - Diversify Role Models

Follow influencers and athletes who showcase a wide range of bodies, abilities, and definitions of health. Exposure to diversity helps protect against narrow beauty ideals.

The Bigger Picture

This isn’t just about TikTok. Social media, in all its forms, has shifted how kids measure themselves. When “likes” become a proxy for self-worth, we’re left with a generation more vulnerable to anxiety, depression, and low confidence.

But here’s the hopeful note: conversations and interventions work. Programs that train students to focus on body functionality, or that broaden their definition of health and fitness, boost resilience.

If schools and families team up, they can reframe the conversation. Instead of asking, “Do I look fit enough?” kids can learn to ask, “Am I strong enough to meet today’s challenges?”

Let’s Talk About It

Your voice matters. Join the conversation:

- What’s the biggest mental health challenge you see in schools today?

- How can schools better support students’ emotional well-being?

- What’s one insight about body image that changed the way you parent, teach, or counsel kids?

Drop your thoughts in the comments or share this article with your network. Because the more we talk about it, the less power that little glowing screen has over the next generation.