Decolonizing School Psychology: Centering Indigenous Voices

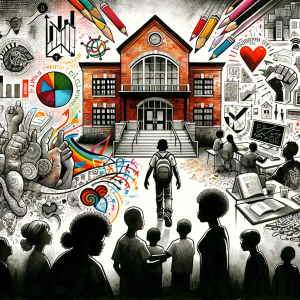

Picture a classroom where every child feels valued, seen, and supported—a place where their cultural identity isn’t just acknowledged but celebrated. Now, imagine the opposite: a system where outdated norms ignore the lived realities of Indigenous students, contributing to cycles of inequity and exclusion. This isn’t just a hypothetical scenario; it’s the reality for many Indigenous children navigating Western-centric education systems today.

A recent Canadian Journal of School Psychology special issue on Indigenous Peoples and school psychology sheds critical light on how to bridge this gap. This blog explores the key insights from the second part of this publication, offering actionable lessons for parents, educators, and school mental health professionals.

Rethinking Success: Learning From the Inuit

Traditional Western measures of student success often prioritize test scores and rigid benchmarks. But for Inuit communities, success takes a more holistic shape, grounded in community values and lifelong learning. One study featured in the journal highlights the Inuit Holistic Lifelong Learning Model, which reframes education to align with Inuit cultural values. This model doesn’t just redefine success; it challenges the notion that one-size-fits-all standards can fairly assess students from diverse backgrounds.

Imagine if your child’s school adopted a similar approach, valuing personal growth, community engagement, and cultural respect alongside academic achievement. How might this reshape the mental health outcomes of students who often feel alienated by current systems?

Building Bridges: The Role of Relationships

Engagement with Indigenous communities requires more than superficial gestures. Another article examines how an urban school psychology team built meaningful relationships with First Nations communities. By acknowledging the land and embedding cultural learning into their practices, they fostered trust and collaboration.

This reminds us that school mental health professionals must go beyond textbooks. Building genuine relationships involves humility, active listening, and a commitment to co-creating solutions with the communities they serve.

Navigating Ethical Dilemmas: A Personal Journey

One of the journal’s contributors shares a deeply personal account of practicing psychology in a remote First Nations community. The author confronts ethical tensions, particularly around dual relationships—a common scenario in close-knit Indigenous communities where roles often overlap. Rather than adhering strictly to Western ethics, the author embraced communal values, using her position to support collective well-being.

This narrative challenges us to rethink professional boundaries. How might adopting a communal ethic enrich the support systems we build for students?

The Representation Gap in School Psychology Research

Representation—or the lack of it—is another pressing issue. A systematic review included in the special issue found that research on Indigenous students in school psychology remains sparse. When Indigenous youth are included, the focus tends to be on assessments like cognitive ability, neglecting broader topics like wellness, resilience, or systemic barriers.

As parents or educators, consider the ripple effects of this gap. If research doesn’t reflect the diversity of student experiences, how can schools hope to serve all students equitably?

A Call to Action: Decolonizing Practice

The issue closes with a powerful commentary urging psychologists to actively engage in decolonization and Indigenization. Melanie Nelson, a Samahquam and Squiala community member, emphasizes the importance of confronting systemic inequities and amplifying Indigenous-led approaches. Her perspective serves as both a roadmap and a challenge: to rethink how school psychology operates at every level, from training to practice.

Why This Matters for Student Mental Health

The implications of these findings extend beyond classrooms and into the hearts of families and communities. Mental health isn’t just about individual resilience; it’s deeply tied to feeling valued and understood within one’s environment. For Indigenous students, culturally responsive practices can be life-changing, fostering not only academic success but also emotional well-being.

As school mental health professionals and educators, we have a responsibility to listen, learn, and act. By embracing these lessons, we can begin to dismantle the barriers that hinder equitable education for Indigenous students.

Join the Conversation

How can schools in your community adopt more culturally inclusive practices? What role do you see for parents in advocating for decolonized education? Share your thoughts in the comments below—and don’t forget to share this blog to keep the conversation going!

Step into the Future of School Psychology!

Engage with the dynamic field of educational mental health for only $5 monthly. This Week in School Psychology offers you a gateway to understanding and applying crucial psychological findings. Enjoy concise, powerful updates that make a difference. Subscribe and join a community dedicated to knowledge and impact. Take advantage of our special yearly rate and lead the way in educational innovation!